In an effort to build a more sustainable future, architects and policy makers are nodding to the past with structures entirely made of timber. From a 70-story timber skyscraper in Tokyo to an all-wood, 200,000-plus square foot university residence hall in Arkansas, constructions that have eschewed steel and concrete for forest-grown materials have been sprouting up across the world. Next up in this timber trend: a Copenhagen neighborhood built fully with wood, with housing for 7,000 people, a school, and a focus on integrating nature with city life.

Danish architecture company Henning Larsen is designing the development, called Fælledby, and working with the city of Copenhagen and public developer By & Havn to bring this all-timber neighborhood to fruition. It's set to be built beyond the city center on a former dumping site, transforming a junkyard into a place where residents can not just live alongside nature but actively participate in bettering it, says Signe Kongebro, the Henning Larsen partner in charge of the project, over email.

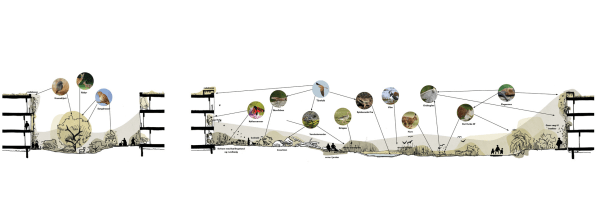

"We hope that to live here is to become a better citizen of nature," she says. "That might mean things as small as not moving a birds nest from your balcony or things as big as maintaining a microclimate on site. This is more necessary today than ever." The neighborhood was designed in collaboration with biologists and environmental engineers, and preserves 40% of the 45-acre project site as undeveloped habitat for local flora and fauna. Nature is also literally integrated into the infrastructure: nests for songbirds and bats will be built into the housing facades; Fælledby will be comprised of three "mini-villages," with the center of each featuring new ponds as habitats for frogs and salamanders; and community gardens will provide flowers to attract butterflies.

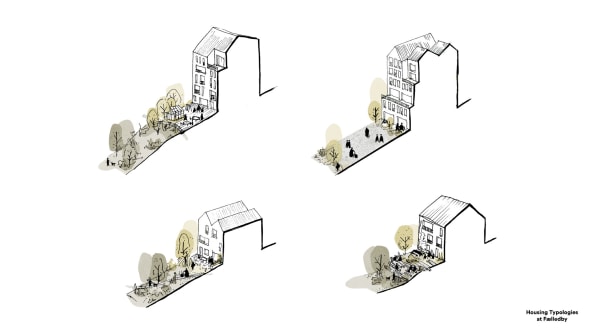

Fælledby's three subsections will be connected by "green corridors" that give residents quick access to the great outdoors—"From anywhere in the neighborhood, you are never more than two minutes walking from wild nature," says Kongebro—and allow local animals a path through the area. Vehicles will be restricted to narrow roads and underground parking, so that they don't distract from nature.

For this neighborhood's construction, Henning Larsen plan to use prefabricated timber panels sourced from partners throughout Europe. "They must of course be sustainably sourced, nontoxic . . . that's just a minimum," Kongebro says. Henning Larsen will become Copenhagen's first new neighborhood built entirely in timber. The Scandanavian city has a rich history in wood construction, with Denmark as a whole most well-known for its "half-timber" architecture that dates back to the Middle Ages. Kongebro sees this new twist on the old ways as a "paradigm shift."

"We really are collectively at the tipping point of a timber revolution," she says. "Timber may not be the right answer for every project, but in the places where it is, we need to push forward with it. Making it part of an urban vision helps to push forward its wider acceptance, which in turn will encourage contractors, investors, and other designers to make it part of their own processes." Because timber captures and stores CO2 during its growth, it's been lauded as a more environmentally friendly material than nonrenewable steel or concrete, which also has a big footprint associated with its construction. There's still some debate about the environmental benefits of all that logging and manufacturing, but it is undeniably having a resurgence, particularly in Scandinavia.

Henning Larsen says the design for Fælledby will be opened to public comment late this summer, and then revised and finalized for a projected 2021 construction start. The neighborhood will not be a shopping or entertainment district—at its core it's for locals, Kongebro says—but will feature a school for 1,500 children along with businesses and services. "This project won't be successful if it's hard to live there and stays empty as a result," she notes.

Part of that success might also lie in how this project inspires others in architecture. "We cannot approach housing—or indeed, any kind of architecture—the way we always have," says Kongebro. "In the instances where we do have to build new, we owe it to our environment and ourselves to do it as conscientiously as possible." She cites the statistic that 70% of the planet's population is expected to live in cities by 2050 as evidence of this need for new, conscious construction. "The city is an inevitable fact," she adds. "In order to ensure the conservation of nature, it is more crucial than ever that the relationship between city and nature is 'both/and,' not 'either/or.' Fælledby is a serious bid on that proposition, and a commitment to making a place where nature is a defining element in its every aspect, not a value proposition."

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90451958/in-this-new-neighborhood-every-building-will-be-made-entirely-out-of-wood

Posted by: malcolmkilee0193641.blogspot.com